When I explain Happily Ever After, I say that we are a network of health and well-being spaces. Oftentimes, I receive questions about our spaces, what that entails and what our specific services are. This misses over a crucial part of what makes us special, the fact that Happily Ever After is a network, is what enables us to approach problems from a different lens than the typical healthcare organization or startup.

Previously in this publication, we have explored adjacent topics such as Honeybee Healthcare which looked at the importance of locally contextualized care, and The Cuban Paradox) which explored the Cuban healthcare system’s outsized patient outcomes. In both articles, we have touched on the importance of community-centred care, but we have yet to address how such care might be structured.

As I’ve already hinted, Happily Ever After believes in the network approach to healthcare- this article explains why.

The fundamentals of networking

To start, it is worth defining what constitutes a network. A network is a system architecture that consists of similar nodes, which are connected together to allow for coordination and communication. Importantly, a network is a flat organizational structure, and it is built of peers which each peer holding roughly equal powers and rights as any other peer.

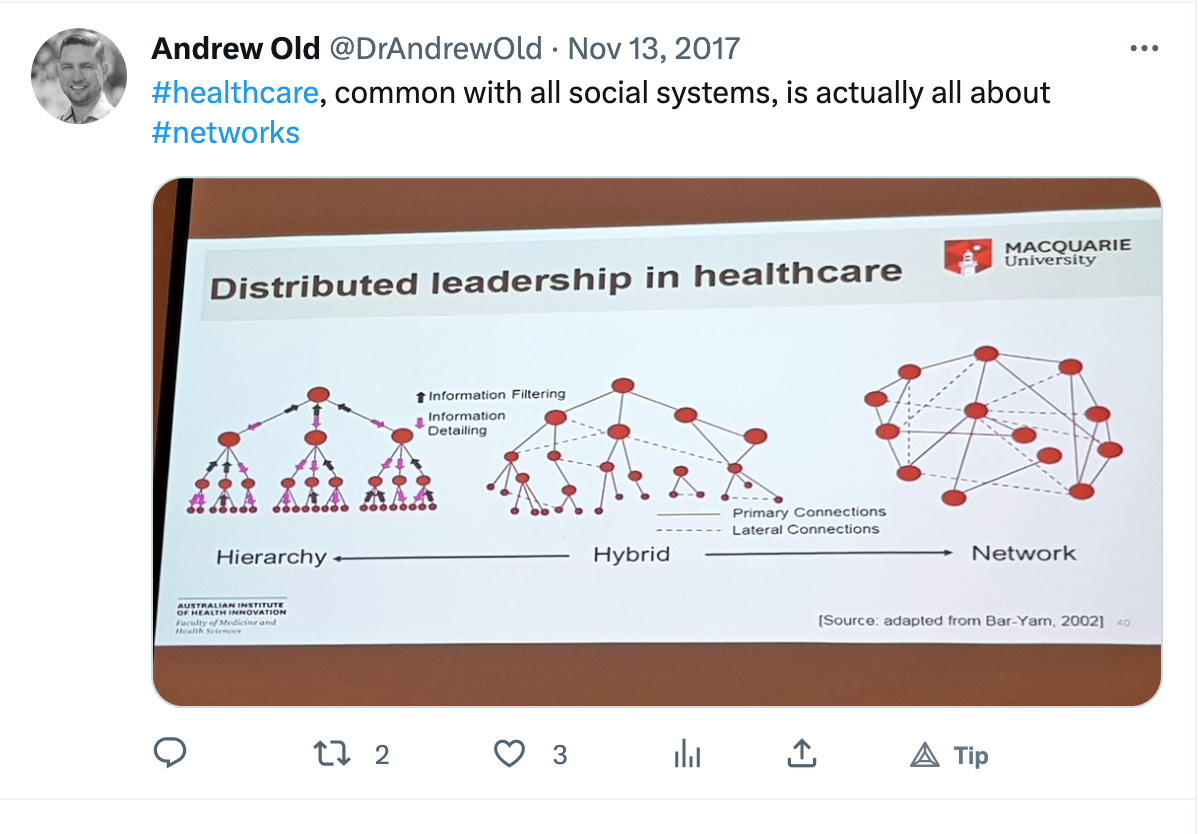

The opposite of the flat network is a tree structure that we are all familiar with - hierarchy. Hierarchies are ordered levels, where each level has more power than the level below. Hierarchies cascade control from the highest level to the lowest, for all tasks that the system must perform. In contrast, networks operate as a heterarchy, which can be unranked (every node has equal power) or ranked in multiple ways depending on the task.

For example, imagine a system with 3 nodes. In a hierarchical model, regardless of the decision that needs to be made, the node with the highest level is the node that has the ultimate deciding authority. But in a network, all three nodes could have the same decision authority in which case the decision is settled by a vote, or there could be a decision-dependent hierarchy that was agreed upon within the network.

Most modern organizations share elements of both heterarchy and hierarchy, although, at the system level, the hierarchy level picture dominates. This is evident from things like organization charts, and widely respected positions of power like the Chief Executive Officer.

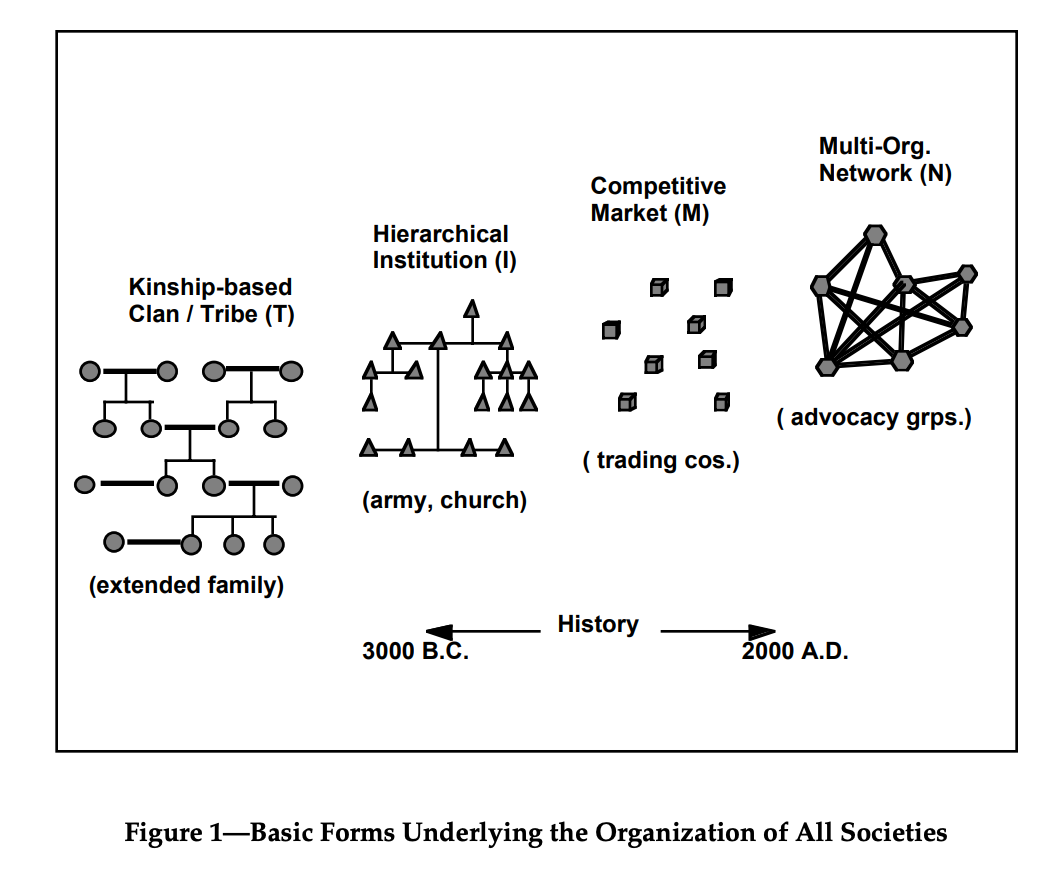

One of the pioneering works in this classification comes from the early internet pioneer, David Ronfeldt from the RAND Corporation. In his paper Tribes, Institutions, Markets, Networks (TIMN), David lays out the narrative of social coordination as progressing through distinct organizational forms.

In his view, each form is a more evolved version of its prior, and he presents a whig account of humanity’s increasing coordination potential.

Good Organizations, Bad Organizations

But to properly understand the utility of networks, it is important that we consider what makes an organization good. Why do we even organize?

The limiting factor of human coordination is trust, through the form of various prisoner’s dilemmas. This lack of trust manifests as a transaction cost, which is the perceived friction of collaborating with an external person or entity. Good organizations lower transaction costs, by attempting to align incentives, create repeated games to overcome the prisoner’s dilemma and lower other techno-social barriers to collaboration.

To give a concrete example, imagine that you are a carpenter looking to build a bed. However, for a specific order, you require the assistance of a wood sculptor for the aesthetic finish. Normally, that would require negotiation between the two parties as to the rewards and expectations of the work. That is the transaction cost incurred.

Instead, if the wood sculptor and carpenter were working at the same company, then they can simply collaborate without worrying about the negotiation, which is conducted automatically by a previously established protocol. Here, a hierarchical institution enforces protocols to reduce transaction costs and improve collaborative output.

So for a given situation, an organizational system is better when it reduces transaction costs more than any other alternative.

Networks are anti-wicked

Looking back to the context of healthcare, our previous articles have gone into detail explaining the interdependence of our health with our social contexts and other goods. This “messiness” is what social scientists call a wicked problem.

The search for scientific bases for confronting problems of social policy is bound to fail because of the nature of these problems… Policy problems cannot be definitively described. Moreover, in a pluralistic society there is nothing like the indisputable public good; there is no objective definition of equity; policies that respond to social problems cannot be meaningfully correct or false; and it makes no sense to talk about “optimal solutions” to these problems… Even worse, there are no solutions in the sense of definitive answers.

In a way, wicked problems cannot be characterized as problems in the scientific-engineering sense. Instead, they are problem-generators, an infinite game which can be played forever, where every applied solution introduces more problems to be solved. This gives ecosystems with wicked problems, a certain quality of aliveness, with the ability to respond and evade applied solutions akin to a bacteria evolving antibiotic resistance.

The solution to a problem generator is a solution generator. A wicked problem can be resolved with an autopoietic system, capable of continually evolving and addressing new problems.

The first is to shift the goal of action on significant problems from “solution” to “intervention.” Instead of seeking the answer that totally eliminates a problem, one should recognize that actions occur in an ongoing process, and further actions will always be needed.

In Honeybee Healthcare, I wrote about the locality-dependence of healthcare which makes everything even more complicated. In healthcare, every local context is an independently wicked problem. A solution that works in one place, could have the opposite effect in a place with a slightly different context.

And this problem is where hierarchies fail. Hierarchies being tree structures, concentrate decision-making power at the top. But the inherent complexity of just one wicked problem, let alone N independent wicked problems is far too much for any person or small group to handle. In contrast, networks act as a swarm of independent units, which are autonomously privileged to come up with solutions that are customized for their local wicked problem.

The practice of rational command and control in hierarchies (OKRs, 10-year-plans, performance reviews) also falls short in the face of complex systems. Instead in Reinventing Organizations, Frederic Laloux calls on network organizations to

“Sense and respond” instead of “predict and control”

By making peace with the reality of wicked problems, networked organizations aim for good-enough solutions that can be iterated quickly - making them natural solution generators. All of this is hard to grasp, how do we measure what works without organization-wide metrics, objectives and goals? And yet it is unsurprising that messy hard-to-quantify problems require messy hard-to-quantify solutions, recalling Ashby’s Law of Requisite Variety:

in order to be efficaciously adaptive, the internal complexity of a system must match the external complexity it confronts.

Networks in the Wild

But this is not to say that, these systems are entirely non-quantifiable. And before dismissing them as one of those idealistic ideas which are practically impossible, it is worth noting that networked organizations are neither new nor impossible.

In 2011, Ewan Ferlie et. al published Public Policy Networks and ‘Wicked Problems’ which reported a shift from hierarchical public service organizations to network forms using evidence from UK-based organizations such as the NHS. The paper specifically highlights the relevance of network forms to wicked problems, citing examples such as the behaviour change in older adults achieved by the Older People’s Network. Even the partial use of heterarchical organization allowed these institutions to cut through multiple jurisdictions and operate in “small, scattered and autonomous” groups.

Additionally, Charles E. Lindblom’s paper The Science of Muddling Through advocates for the iterative style of approaching wicked problems, even in the absence of clear overarching objectives and plans. Instead in his view, the rational comprehensive method which attempts to centralize, predict and control the outcomes of a policy is in fact the actual practical impossibility.

Policy is not made once and for all; it is made and re-made endlessly.

An example we admire in Happily Ever After is Buurtzorg Nederland, which was established in 2006 with a network-based model of home-based nursing care. Buurtzorg’s network consists of small independent squads of nurses working to serve a particular neighbourhood’s care needs. It consistently reports some of the highest client and workplace satisfaction rates of any healthcare organization and has recently expanded its model of care to the UK.

Cautions for the Network Builder

The network approach is not without its challenges. When Buurtzorg ran the Transforming Integrated Care in the Community (TICC) initiative to replicate heterarchical principles into existing institutions, it found resistance working against contexts where network-thinking values, cultures and goals were not shared.

In Formal Structures are Myth and Ceremony, John Meyers writes about the organizational imperative to comply with existing norms of operation. He asserts that organizational survival goes beyond achieving efficiency in the desired purpose, crucially because of the need to maintain relationships with institutional environments for legitimacy.

Organizations that incorporate societally legitimated rationalized elements in their formal structures maximize their legitimacy and increase their resources and survival capabilities.

This is especially important to organizations that depend on the ceremonial demands of external institutions. Unfortunately, healthcare is one of those institutions with rules which impose costs on iconoclastic but potentially more efficient organization structures. This makes Buurtzorg’s local success even more surprising, as these factors appear to play a much larger role in projects like the TICC.

Additionally, the legal and technological infrastructure to support these organizational forms is nascent. Adjacent experiments such as Decentralized Autonomous Organizations offer some hope on this front by providing early prototype tools to run networked organizations.

Networks Work

Healthcare, education, transportation and beyond hold many wicked problems waiting to be solved, and heterarchies seem well poised to revolutionize organizations in civil society. The autonomous social sector has long been torn between government bureaucracy (NGOs) and market pressures (social enterprises), and networks offer a third modality that could be values-aligned to deliver public goods and services.

Yet, there remains lots of work to do, to see if networks will play a big role in solving these problems. From building new organizational tools to writing policy papers to increase the legitimacy of networked organizations, there are many hurdles for the builders of networks to cross.

For our part, Happily Ever After, continues to believe that networks are the optimal way to achieve our purpose of universally accessible preventive care. We are leading the charge in building tools and protocols to help other networks follow our lead. If you believe that networks work too, get in touch and join us on our mission :)