In the winter of 2006, beekeepers started reporting a sudden loss of bee colonies. Curiously, these colonies were displaying symptoms inconsistent with known causes of honey bee death. This was the start of a phenomenon known as colony collapse disorder (CCD), in which there is a sudden loss in the number of colony worker bees, leaving behind a queen bee and abundant food reserves.

Researchers have identified a few potential causes for this phenomenon such as parasites, pesticide poisoning and poor environmental nutrition. But the cause of CCD is always assumed to be at the colony level, not at the individual level.

In fact in most sources of literature, bee health is always addressed at the colony level. Almost all interventions are administered at the colony level through environmental design, support, tools and systems.

When it comes to colony health, many factors of individual well-being are directly correlated to colony well-being and systemic health issues. But this article is not about bees, and neither is it trying to imply that human health is similar to bee health. But it seems that in social organisms, well-being should be explored at the colony level just as deeply or more deeply that the individual level.

This topic was briefly discussed in The Cuban Paradox, where the Family Doctor and Nurse program, instituted in the 1980s, is often cited as the driver of Cuba’s impressive average life expectancy relative to GDP. Cuba’s public health initiatives specifically focus on community-centered rather than individual-centered care, where care is catered to a local community’s needs.

The shift toward community-driven preventive care is not isolated to Cuba, although to its credit it was the first to test the system on a large scale. For the last decade, many organizations across the world have been pushing for more of this type of care: The Kaiser Foundation, The National Prevention Council, and The British Society of Lifestyle Medicine to name a few. The terminology used differs (integrative healthcare, lifestyle medicine, preventive medicine), but the core principles of these organizations paint the same broad strokes.

They are called the social determinants of health (SDOH) which are various factors of health beyond clinical medicine. The SDOH show that when thinking about well-being, up to 89% of individual health depends on non-clinical factors.

If zip code is a stronger predictor of health than genetic code, then maybe human health is not so different from the bees.

Major categories of colony health (nutrition, oxidative stress resistance, and immunity) were impacted by apiary site - Nature

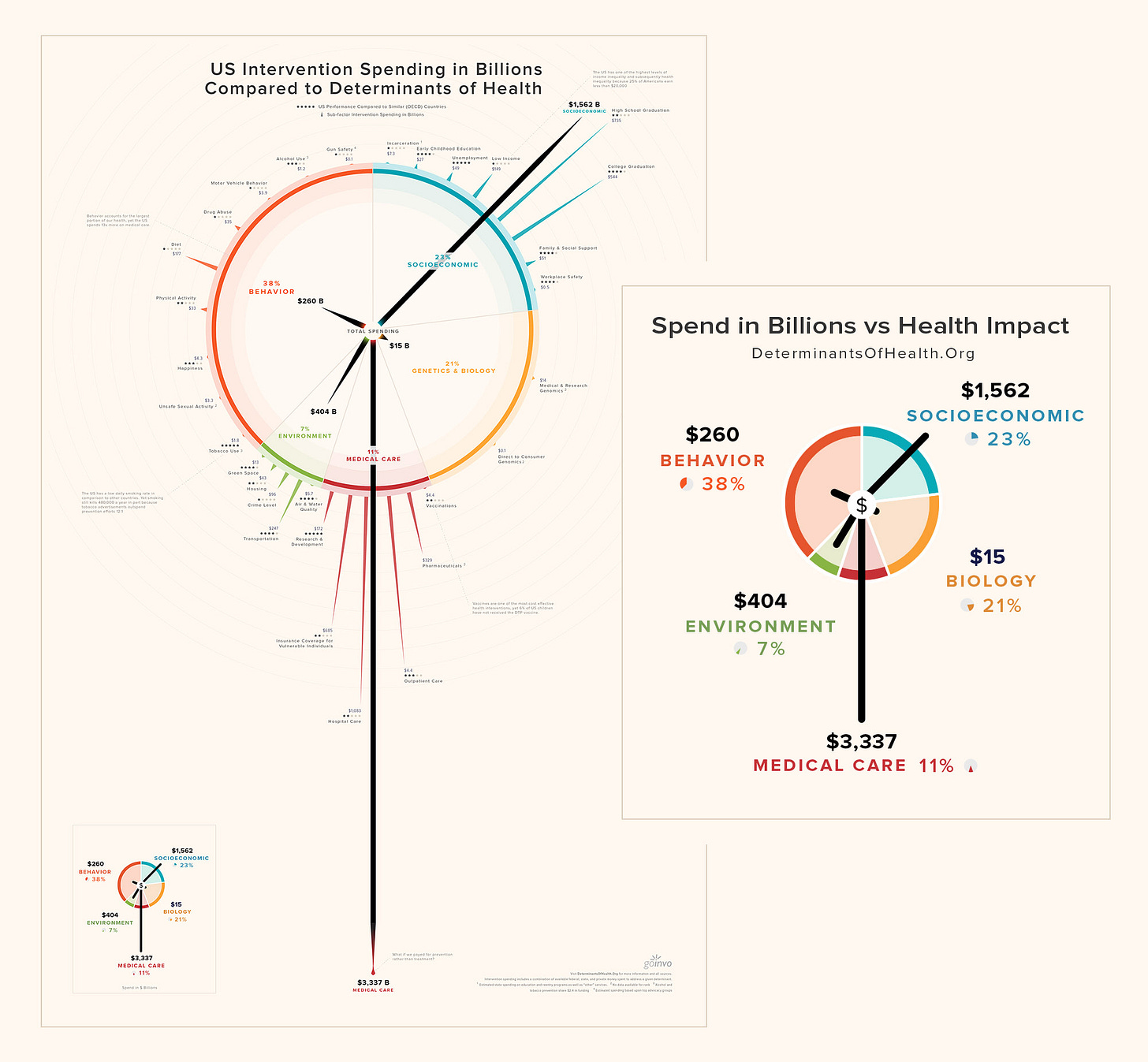

GoInvo, a healthcare UX agency, illustrates this dynamic in a poster comparing percentage contribution to well-being with the amount of capital spent on it. This diagram would vary between jurisdictions, but generalizes to a systemic overvaluation of clinical services, as opposed to other health factors. These costs are inevitably passed on to everyone, either through taxation, high insurance bills or expensive medical care.

The average 1960 worker spent ten days’ worth of their yearly paycheck on health insurance; the average modern worker spends sixty days’ worth of it, a sixth of their entire earnings. - Slate Star Codex

Healthcare as social support

Clued in by the name, social determinants of health, a large part of healthcare has to do with social support. This means that policies and practices in non-health sectors have an impact on health and health equity. The National Prevention Strategy outlines 4 directions to address the problem areas:

-

Healthy and safe community environments

-

Clinical and community preventive services

-

Empowered people

-

Elimination of health disparities

Other preventive care advocates echo these themes. Happily Ever After, as an organization aims to directly address the first three factors, and advocate for the fourth.

Social support behavioral code (SSBC)

When thinking about social support, it is useful to bring in a framework like the SSBC to understand our current position. The SSBC lists the different kinds of social support that can be provided:

-

Informational Support: direct informational support, advice, sharing of knowledge

-

Tangible Support: goods and services

-

Emotional support: mental health support to deal with situations

-

Esteem support: compliments, validation and motivation

-

Network support: access to companions, presence and care

The existing healthcare system provides strong informational support, and tangible support. It is only just catching up to providing emotional support. Esteem and network support are mostly provided by existing personal friend and family networks.

Critically, right now, most of this support is retroactive, after a diagnosis has been made. In contrast, an approach in line with the social determinants of health pushes these support mechanisms to be proactive. By their nature of being social, a preventive approach is highly dependent on local contexts.

Research should be in dynamic relation with local agents of change in the environment - a recommendation by the National Prevention Strategy

Local health is buzzing

Defining locality

In considering the various contexts that may be relevant for healthcare, it is important to first define the concept of locality. Typically, locality refers to a specific physical community. However, for a web-based organization like Happily Ever After, locality can also encompass cyber-physical spaces.

In today’s interconnected world, social structures are often fluid and not necessarily tied to traditional family units or physical locations. People may maintain relationships with individuals they have never met in person, and locality can be understood as networks of people and shared memes rather than a specific physical location. In this sense, neighborhood and community become multi-dimensional constructs existing within cyber-physical space, rather than being tied to a specific physical location.

Health in cyber-physical localities

An effective preventive care program aims to make itself redundant as soon as possible: by providing individuals with the tools and autonomy to apply the techniques of lifestyle medicine. This comes down to the 5 key pillars of human well-being: nutrition, exercise, sleep, mental health and relational health. Some examples of statements reflecting these pillars are:

-

“Sleep 7-8h a day”

-

“Walk 10,000 steps a day”

-

“Eat right!”

-

“Avoid stress”

-

“Loneliness kills”

Easier said than done. The statements lack context but apply broadly and globally, which explains their widespread usage in global health media. To illustrate, the notion of “eating right” is highly varied between people from different socioeconomic, ethnic and genetic backgrounds. The WHO mentions this as well, on their page on healthy diets

Diet evolves over time, being influenced by many social and economic factors that interact in a complex manner to shape individual dietary patterns. These factors include income, food prices (which will affect the availability and affordability of healthy foods), individual preferences and beliefs, cultural traditions, and geographical and environmental aspects (including climate change).

This means that for health guidance to be relevant to a community, the local context must be re-injected into the statement. All of the required context corresponds to an individual’s cyber-physical locality.

-

Genetics: influenced by the family network

-

Behavior: influenced by peers and social network

-

Environment: influenced by physical locality

-

Social circumstances: influenced by family network and social network

Observing how the social determinants of health are highly driven by local factors, explains why generic health advice is rarely actionable. Preventive care is complex and personal to an individual and their locality.

Population Health

What colony health is to bees, population health is to humans - an approach of integrative and locality-based care that reduces health inequities, promotes health span and improves health outcomes. The domain of population health also an aspect of the Quadruple Aim, which outlines four goals for any healthcare system, alongside reducing costs, patient experience and caregiver well-being.

Although bee health and human health are vastly different, there is genuine opportunity in exploring the domain of population health in at least as much detail as we have explored bee colony health. It opens new frontiers in how care could be administered, and poses many important questions to our healthcare systems today. How can novel systems balance the resources allocated to each social determinant of healthcare, to avoid overweighting clinical medicine? How could communities be taught the skills to gain autonomy over their own well-being? How could health promotion and communication be contextualized to the locality in which it is delivered?

And how can care be made relevant, approachable and integrated into everyone’s lives? These are questions that Happily Ever After takes to heart and is pursuing while building community-centred preventive care. We believe that experimentation at the intersection of public health principles, technology and health science is key to uncovering more problems, and perhaps even solutions in the domain of population health.

If these questions excite you, join us in our journey to build a community of care that delivers on the Quadruple Aim.