Data structures influence data control

Global identity systems which power personal data stores could be the way to create web apps that maximise human autonomy

Web 3 is a conversation about control. The core principle of the new web is to return control over all aspects of digital life to its rightful users, in contrast to the internet oligopoly we see today. Organizations like Disco, Ceramic Network and Snapshot are reimagining the web as a place where individuals have a say in who they are, what data they own and how the digital platforms they use are governed.

But it is difficult to initiate a transition away from incumbent web architecture without first understanding the dynamics that have led to today. The self-sovereign internet experience is not one that can be simply strapped to our existing system. It demands a first-principles approach to designing an ecosystem that drives away from the consolidation of identity, data, and ultimately, digital power.

A book with hyperlinks

In 1989 when Tim Berners-Lee invented the World Wide Web, he set out to solve the problem of finding and transferring hypermedia from servers that generated content to clients that consumed them. The Hypertext Transfer Protocol (HTTP) was designed to solve this problem, as an application layer protocol for distributed, collaborative, hypermedia information systems.

Hypermedia was a novel concept for the early internet, for the first time, you could have hyperlinks: permissionless links that led from one resource on the internet to any other. This was enabled by a broadly accepted standard called the Uniform Resource Identifier (URI). Every website link that exists today, for example https://www.google.com, complies with the URI standard.

By the year 2000, 500 million people were using the web. Most of the web back then consisted of janky sites with search bars viewed over a 56k dialup connection. Looking at these early websites, the focus on hyperlinks and web navigation between pages is clear. Amazon’s website heavily relied on hyperlinks to different pages, each with its own unique URI. Accessing different resources from content providers like Amazon, wasn’t just a part of the internet, it was the internet. The read-only web was all about links, pages and resources.

IP addresses as Identity

URIs are only one part of the problem. Upon receiving a URI, a browser must find the correct device to request the resource from. To accomplish this, each device has its own unique identifier called the Internet Protocol (IP) address.

To resolve a URI into an IP address, the browser employs the Domain Name Service (DNS) system, to convert human-readable hostnames (google.com) into IP addresses (172.217.16.23). Without delving into excessive detail like NAT traversal, private networks and DNS records, IP addresses form the foundation of referencing and identifying devices on the internet.

However, IP addresses change often. A single device’s IP address would change as it moves through different networks, for example, a mobile phone moving from a 5G network to a home wifi network would have entirely different IP addresses. This makes IP addresses terrible forms of identity, it is difficult to provably identify a person or even a device based on its IP address.

But IP addresses are one of the only forms of “native” identity in the internet protocol suite, albeit a rudimentary one.

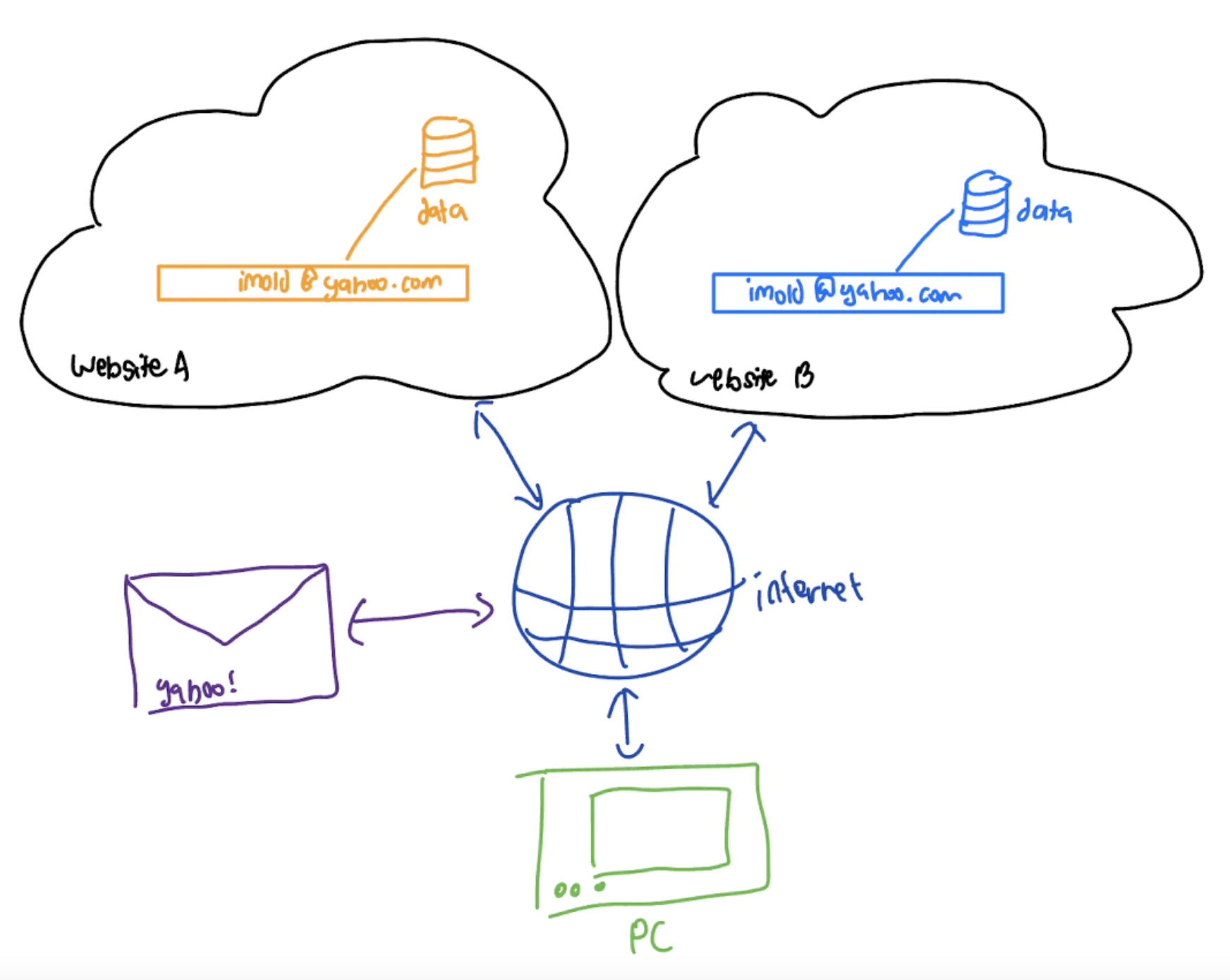

Rather than deal with the whims of changing IP addresses, early web applications often rolled their own authorization, authentication and identity systems. Every website and application had its own internal User structure, with the associated identity, username, password and other personal information.

Emails became a form of defacto identity, through platforms like Yahoo! and Hotmail. Email addresses were static and could be contacted through a standard peer-to-peer protocol: SMTP.

This email identity allowed applications to store and persist user-related data between login sessions. Amazon could remember what items a user had added to their cart, and Google could remember what searches they had previously made. In the read-only web, where websites were just content providers, this web architecture worked extremely well and enabled many useful features.

Consumer Clients → Creator Clients

The client-server architecture was designed for resource-generating servers to serve resource-consuming clients. In 2006, everything was changing and a new internet paradigm was on the rise.

Web 2 is widely described as the user-generated web, and includes platforms like Facebook, Instagram, Tiktok and YouTube where the value of the platform comes from the data generated by its users. Web 2 inherited much of the legacy infrastructure that powered websites before it, the earliest iteration of Facebook was a server-side rendered PHP site.

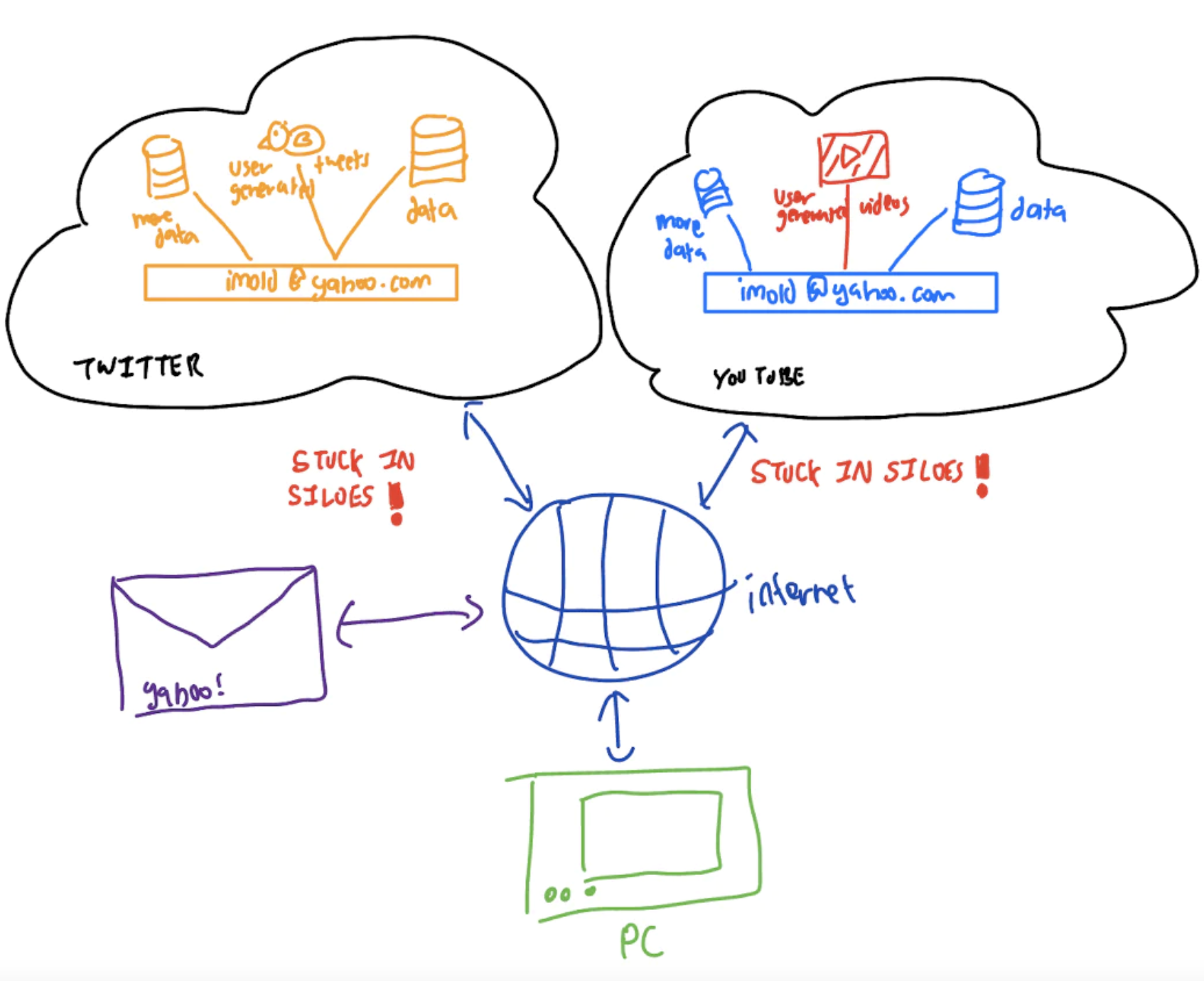

This includes the client-server architecture and the email-based identity system that enabled earlier websites to achieve user persistence between login sessions. Except now, the User structure was getting increasingly bloated, as users pumped out the videos, tweets and posts that brought the platform companies their riches.

Products evolve fast, but protocols evolve slowly. The infrastructure and design principles that formed the early web were rapidly outpaced by the web app and mobile revolution in quick succession. Using the internet in 2022 is radically different from the hyperlink-ridden early days of the internet, but many legacy protocols including URIs and request-response REST APIs are still used heavily in modern applications.

Without a native identity system, the bloated User structures held data in silos that were only accessible to the platform companies running the servers. The legacy data structures that worked well for the read-only web became the means for the centralized data oligopoly that is seen today. Email identity evolved to become “Social Login” protocols like OpenID Connect and OAuth, creating hubs of proprietary user identities.

The initial client-server design of web architecture is what gave rise to this centralization. While companies like Facebook have been quick to monetise and monopolize their data advantage, they are not solely to blame for the current system.

Data architecture from first principles

To preserve human autonomy online, applications should be designed with the ability to migrate and move user-generated data between competing platforms: resulting in a form of credible exit. This prevents extractive exploitation of users and aligns incentives for digital platforms to provide competitive services.

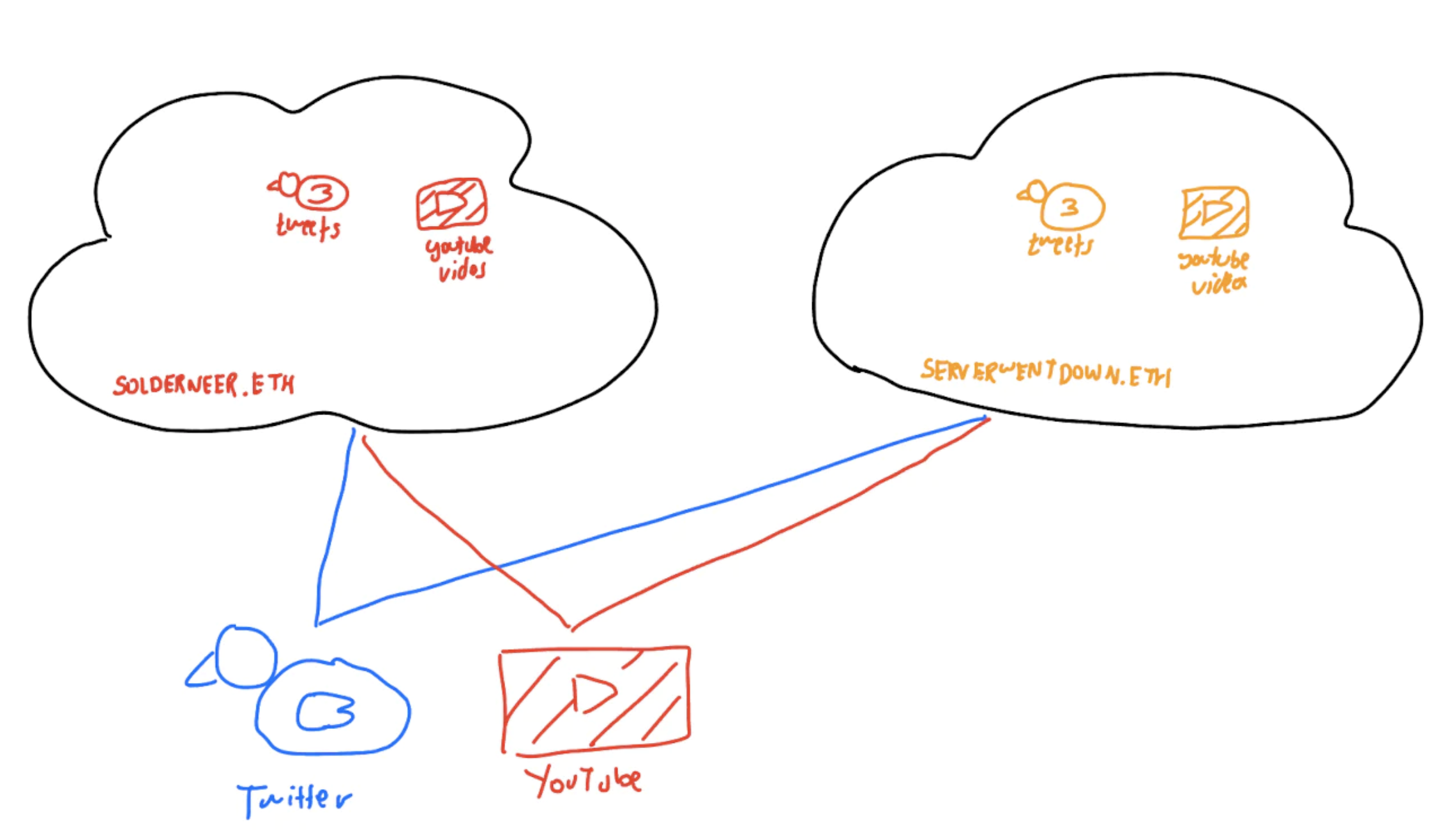

A pre-requisite for that future is self-sovereign and internet-native identity. Without internet-native identity, it is impossible to link data to its creator and thereby enforce data ownership rights. Without self-sovereign identity, it is impossible to trust-lessly ensure that a single player is unable to aggregate and control a large number of identities. This sort of identity system is currently being made possible through public key cryptography and decentralized identity systems like DID and UCAN.

Data stores could then be attached to global user identities rather than application-specific identities. In that way, the holder of a digital identity has the final say in which applications access their data and in what way, through cryptographic methods like W3C’s Verifiable Credentials.

Global identity systems which power personal data stores with broad interoperability would be the first-principles answer to creating web applications that maximise human autonomy. Some projects like Solid Protocol and Distributed Web Node are already working towards that ideal.

The lessons learnt from history are a reminder of how data structures influence data control, and the importance of designing systems that nudge the world towards being a more self-sovereign place. Only by thinking through the designs of these systems will the vision of digital human autonomy, finally be realized.